Historical novel evocatively depicts Nazi-occupied Rome, stumbles on famous priest’s characterization

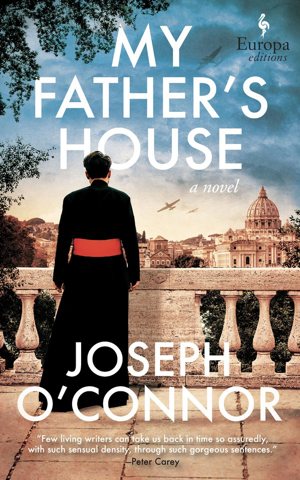

“My Father’s House (The Rome Escape Line Trilogy, 1)” by Joseph O’Connor. Europa Editions. (New York, New York, 2023). 440 pp., $27.

In his novel, “My Father’s House,” Joseph O’Connor presents a semi-fictionalized version of the story of Msgr. Hugh O’Flaherty — probably best known to Catholics by his moniker “the Scarlet Pimpernel of the Vatican” — and his allies, who rescued thousands of Jews, POWs and Italian resistance fighters from the Nazis.

While “My Father’s House” is a skillful portrayal of the evils of fascism and the fortitude demanded of those who would oppose it, its depiction of Catholic spirituality unfortunately leaves something to be desired.

Atmosphere and ambience are the work’s most potent ingredients, as O’Connor convincingly recreates the world of Nazi-occupied Rome. Readers who have had the privilege of visiting the Eternal City will find themselves chilled by his ability to evoke their enchanted memories — favorite hole-in-the-wall cafés, glittering famous fountains, doves in St. Peter’s Square — and then deface them with machine gun fire, swastikas and rampant starvation. The reality of life under fascism is starkly portrayed, with few punches pulled: beyond even the threats of famine and casual violence looms the torture chamber in the basement of the former German Embassy, the fate awaiting Msgr. O’Flaherty — “Hugh” to his friends — if he is caught by Hauptmann (the novel’s fictional stand-in for S.S. Chief Herbert Kappler).

Against this grim backdrop, the heroism of Msgr. O’Flaherty and his “choir” shines all the brighter. The book’s constellation of characters, several of them based on real members of the Rome escape line, are witty, brilliant, angry, flawed, devoted, human — and brave. It is impossible to read this book and not come away with a greater appreciation of the courage of those who defied the evil of Nazism, and the risks they undertook.

By far the novel’s most suspenseful section is the night of the Rendimento (“performance” in Italian) on Christmas Eve, in which the game of cat-and-mouse which has been playing out between Msgr. O’Flaherty and Hauptmann comes to its heart-thudding conclusion. O’Connor’s careful work establishing the atmosphere of dread in the first portion of the novel pays dividends in the final third, as Msgr. O’Flaherty and the choir attempt to deliver several “drops” of money — enough to move every concealed POW and Jewish escapee out of Rome. The threat is real, and O’Connor does a masterful job of making the reader face up to it.

Insofar as it is an immersive — and therefore terrifying — look into life under fascist occupation and the true cost of resistance, “My Father’s House” thoroughly accomplishes the goal it set out for itself.

One aspect in which it disappoints, however, is that for a book ostensibly about a famous priest, its depiction of Msgr. O’Flaherty’s inner life is not altogether convincing. For one, the reader rarely sees the main character talk to God. That’s not to say the reader doesn’t see him pray: Msgr. O’Flaherty celebrates Masses, prays rosaries, hears confessions and goes through all the rituals expected of men of the cloth. But despite fiction being one of the rare art forms where the reader can know a character’s inner thoughts, the spiritual life, the direct communication between God and this Catholic priest, is something the novel rarely shows. The rare moments where it does show this sometimes smack of exasperation and condescension from beyond the page, as if the author considers Msgr. O’Flaherty’s religion a hindrance to the character, instead of his motivation.

One might accuse me of being unfair; after all, O’Connor didn’t set out to write a book of Catholic fiction. The trouble is that he did set out to write a book about a Catholic priest, and writing a work of fiction about any subject, let alone a real person, requires getting into the character’s head. In this case, the author unfortunately seems to have used the trappings of Catholicism (incense, vestments, plainsong chants and statues of saints — all the “smells and bells,” as it were) to avoid getting into the head of a practicing Catholic — to avoid interacting with the thought processes and motivations of a character who actually believes, whether fervently or falteringly, in his faith.

O’Connor is an excellent writer, and the story is compelling; Catholic readers will doubtlessly enjoy seeing one of their own engaged in feats of daring-do to save innocent lives and defy fascism. Nevertheless, this reviewer wishes that the author would have approached the interior life of a devout Catholic at least seriously enough to convincingly portray it, instead of avoiding the challenge by relying on aesthetics.

Reichert is publications administrative coordinator at The Catholic Spirit. She can be reached at reichertm@archspm.org.