The U.S. Supreme Court on June 27 limited the ability of federal judges to issue nationwide injunctions in a case concerning the Trump administration’s executive order to end birthright citizenship for children born in the U.S. to parents without legal status or temporary visa holders, without addressing whether or not the order itself is constitutional.

The high court, in a 6-3 decision, found that universal injunctions issued by federal judges to block that order resulting from lawsuits filed over it “likely exceed the equitable authority that Congress has granted to federal courts.”

The ruling will allow — in part — an executive order President Donald Trump signed within hours of returning to the Oval Office in January that sought to end the practice of birthright citizenship for these children to be enforced. However, it also left in place the ability for judges to constrict it for those parties in lawsuits over it.

After Trump signed the order, it was promptly challenged in court by some parents of children whose citizenship would be impacted, who argued it unlawfully violated the 14th Amendment. The Trump administration argued that federal judges improperly blocked the order amid those lawsuits.

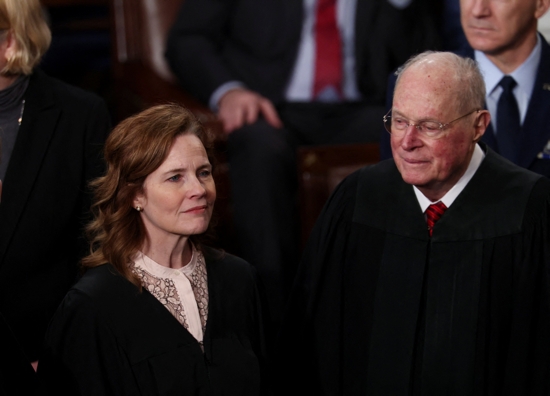

Writing for the majority, Justice Amy Coney Barrett said, “Federal courts do not exercise general oversight of the Executive Branch; they resolve cases and controversies consistent with the authority Congress has given them.”

“When a court concludes that the Executive Branch has acted unlawfully, the answer is not for the court to exceed its power, too,” Barrett said.

Barrett argued that a universal injunction against the order was not strictly necessary to provide those with standing to sue for relief from the order.

“Here, prohibiting enforcement of the Executive Order against the child of an individual pregnant plaintiff will give that plaintiff complete relief: Her child will not be denied citizenship,” Barrett said. “Extending the injunction to cover all other similarly situated individuals would not render her relief any more complete.”

Barrett, however, stressed, “The applications do not raise — and thus we do not address — the question whether the Executive Order violates the Citizenship Clause or Nationality Act.”

In a dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote, “Children born in the United States and subject to its laws are United States citizens. That has been the legal rule since the founding, and it was the English rule well before then.”

Trump’s order to effectively rewrite the long-standing legal interpretation of birthright citizenship, she said, was to “repudiate” the practice.

“The Government does not ask for complete stays of the injunctions, as it ordinarily does before this Court,” Sotomayor said. “Why? The answer is obvious: To get such relief, the Government would have to show that the Order is likely constitutional, an impossible task in light of the Constitution’s text, history, this Court’s precedents, federal law, and Executive Branch practice. So the Government instead tries its hand at a different game. It asks this Court to hold that, no matter how illegal a law or policy, courts can never simply tell the Executive to stop enforcing it against anyone. Instead, the Government says, it should be able to apply the Citizenship Order (whose legality it does not defend) to everyone except the plaintiffs who filed this lawsuit.”

“The gamesmanship in this request is apparent and the Government makes no attempt to hide it,” she added. “Yet, shamefully, this Court plays along.”

Sotomayor argued, “No right is safe in the new legal regime the Court creates.”

“Today, the threat is to birthright citizenship,” she said. “Tomorrow, a different administration may try to seize firearms from lawabiding citizens or prevent people of certain faiths from gathering to worship. The majority holds that, absent cumbersome class-action litigation, courts cannot completely enjoin even such plainly unlawful policies unless doing so is necessary to afford the formal parties complete relief. That holding renders constitutional guarantees meaningful in name only for any individuals who are not parties to a lawsuit.”

In comments to reporters at the White House, Trump celebrated the ruling, arguing, “We’ve seen a handful of radical left judges effectively try to overrule the rightful powers of the president to stop the American people from getting the policies that they voted for in record numbers.”

Trump said as a result of the ruling his administration would “promptly file to proceed” with several policies he said “have been wrongly enjoined at a nationwide basis, including birthright citizenship, ending sanctuary city funding, suspending refugee resettlement, freezing unnecessary funding, stopping federal taxpayers from paying for transgender surgeries and numerous other priorities of the American people.”

The 14th Amendment states, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

Despite arguments from Trump when he signed the order in January and ones he has repeated since that the U.S. is “the only country in the world that does this,” the United States is one of at least 30 countries, including Canada and Mexico, in which the principle of “jus soli” or “right of soil” applies. This legal principle grants citizenship at birth without restrictions, regardless of the citizenship status of the parents. Most of those countries are located in the Americas, and scholars trace the origins of the practice to colonial times. It also has origins in English common law.

Trump’s order, part of his administration’s broader effort to implement his hardline immigration policies, directed federal agencies to stop issuing passports, citizenship certificates and other official documents to children born in the U.S. to parents without legal status or temporary visa holders. The order would not apply retroactively, Trump said.

Federal judges in the states of Maryland, Massachusetts and Washington subsequently blocked Trump’s directive nationwide, arguing it was in apparent violation of the 14th Amendment.

But challenges to the merits of that order will likely continue, and may be addressed by the Supreme Court at a later date. The court paved the way for it to be enforced in 30 days, although the details of how the policy would be implemented were not immediately clear.

The executive order itself is among the Trump administration’s immigration policies that have been criticized by the U.S. bishops.

Kate Scanlon is a national reporter for OSV News covering Washington.